The Syrian Crisis - An Overview (Mar 11 - Oct 15)

|

Author: Mark Miceli-Farrugia |

|

Dated: 2015-10-24 |

|

Uploaded: 2019-08-31 |

|

Last Edited: 4 years ago |

THE SYRIAN CRISIS – AN OVERVIEW

1. Brief Lead-Up to Current Crisis

2. The Parties to the Conflict

3. A Conflict-Mapping Guide of Syria

4. The Geopolitics in Syria

5. The Issues

6 The Only Solution Possible

7 Parallels with Conflict Analysis Theories: For ease of reference, we shall evaluate pertinent theories used to analyze Syrian events as we record them.

1. Brief Lead-Up to Current Crisis

1a. Escalating Events [1]

March 2011: Pro-democracy protests erupted in the southern city of Deraa after the arrest of some teenagers who painted revolutionary slogans on a school wall. Security forces opened fire, killing several demonstrators. This triggered nationwide protests that demanded Pres. Assad's resignation.

July 2011: Government use of force to crush dissenters hardened protesters' resolve. Hundreds of thousands took to the streets across the country. Opposition supporters eventually began to take up arms, first to defend themselves, later to expel security forces from their local areas.

2012: Syria descended into civil war as rebel brigades formed to battle government forces for control of cities, towns, and the countryside. Fighting reached Damascus and second city of Aleppo.

June 2013: The UN estimated that 90,000 people had been killed in the conflict.

February 2014: A UN Security Council resolution demanded that all parties end the "the indiscriminate employment of weapons in populated areas."

August 2014: The UN estimated casualties at 191,000.

Conflict soon acquired sectarian overtones, pitching Sunni majority against Pres. Assad’s Shia Alawite sect. It then drew in neighboring countries and world powers. The rise of Jihadist groups, including Al-Qaeda-aligned Al-Nusra and Islamic State (ISIS), pitted Shia against Sunni and internationalized the conflict further.

IS spread its influence across parts of Syria and Iraq, proclaiming a "caliphate" and drawing foreign volunteers by the thousands. Led by former commanders of Saddam Hussein’s army, IS claimed ever more land in northern Syria. An emboldened IS launched an offensive in Iraq, routing the army the U.S. had created there and captured the country 's second largest city, Mosul.

The UN reported that, in some instances, civilian gatherings had been deliberately targeted and massacred - sometimes with brutal barrel bombs and with lethal sarin nerve gas. Pres. Assad acceded to the UN’s demands that he completely destroy his Government’s chemical agents by August 2014.

UN accused IS of launching a campaign of terror in northern and eastern Syria, and of perpetrating hundreds of public executions and amputations on those who refused to accept its rule. IS fighters were also accused of carrying out mass killings of rival armed groups, including security forces and religious minorities, and of beheading hostages, including several Westerners.

Theoretical Parallel - Azar's 'Protracted Social Conflict' Theory [2]

Azar’s theory of ‘Protracted Social Conflict’ predicts that the prolonged struggle by communal groups for basic needs like identity, security, recognition, fair access to political institutions, and economic participation leads to a spiralling sequence of violent events. He also suggested that, when two key needs like identity and security had been challenged over a protracted period, insurgents would probably only be satisfied by a radical change in their society’s structure.

The problems in Syria started out as peaceful pro-democracy protests by young teenagers. The Syrian Government, which was run by an elite minority of Alawite Shiites reacted brutally, opening fire and killing some demonstrators. Assad’s inability to respond effectively to his constituents’ needs undermined his legitimacy.

The shooting of unarmed protesters was a trigger event that, in due course, provoked nationwide armed rebellion with international repercussions. The general recognition of the students' grievances led to a collective protest that, in turn, was met by further coercive measures. The failure of the government to ever consider instrumental co-option led to an upward spiral of violent clashes and, eventually, to open warfare. According to Azar’s theory, the most logical solution is regime change.

Evaluation: Azar’s theory is dynamic, and has both descriptive and predictive value. It is important when used in combination with substantive theories like Burton’s.

1b. The Refugee Crisis [3]

Almost 4 million persons have fled Syria since the start of the conflict, most of them women and children - one of the largest refugee exoduses in recent history.

Neighboring countries have borne the brunt of the refugee crisis, with Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey struggling to accommodate the flood of new arrivals. During 2013, as conditions in Syria deteriorated, the exoduses accelerated dramatically.

A further 7.6 million Syrians have been internally displaced, bringing the total number forced to leave their homes to more than 11 million - half of the country's pre-crisis population.

In December 2014, the UN launched an appeal for $8.4bn to provide help to 18 million Syrians. A UN report in March 2015 estimated that 80% of the Syrian people were living in poverty - 30% of them in abject poverty. Syria's education, health, and social welfare systems are also in a state of collapse.

In early September 2015, the news media broadcast videos of drowned child- refugees being washed face-down onto European shores. Within days, German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s pledged to grant asylum to genuine refugees, raising the prospect of more than a million migrants reaching the EU this year [4]. Most EU partners have balked at the social and financial implications of such a policy.

Theoretical Parallels - John Burton's 'Basic Human Needs' Theory [5]

Syrian crisis described above demonstrates how students' demands for recognition and political access rapidly escalated into a war expressing demands for religious identity (via open Sunni-Shia clashes), cultural identity (the Kurds' demands for autonomy) and security (as demonstrated by the unprecedented flight of refugees).

Evaluation: Burton’s theory is static, being mostly concerned with describing substantive needs. It is invaluable when used in combination with predictive theories like Azar’s.

2. The Parties to the Conflict

The Syrian war has transformed into a full-blown proxy war, involving not only Syria's neighbours and regional powers, but also Western countries and numerous 'foreign fighters' from more than 25 countries. The following table was inspired by an article appearing in Business Insider [6]

PROXY WARS IN SYRIA

|

SYRIAN GOVERNMENT SUPPORTERS |

SYRIAN GOVERNMENT FORCES SHIA |

REBEL FIGHTERS IN SYRIA SUNNI |

REBEL SUPPORTERS IN SYRIA |

|

RUSSIA |

ASSAD’S TROOPS |

IS¹ (Theocratic) AL-NUSRA² (Semi-Theocratic) |

SAUDI ARABIA QATAR KUWAIT |

|

IRAN |

IRANIAN TROOPS |

||

|

IRAQ |

HEZBOLLAH |

||

|

|

MILITIAS |

||

|

|

|

FREE SYRIAN ARMY³ (Secular) |

TURKEY UK USA FRANCE JORDAN |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

|

--------------------------KURDS-------------------------- |

USA? |

|

¹ a.k.a. as ISIS; ² a.k.a. Al-Qaeda; ³ a.k.a. West-backed Syrian National Coalition

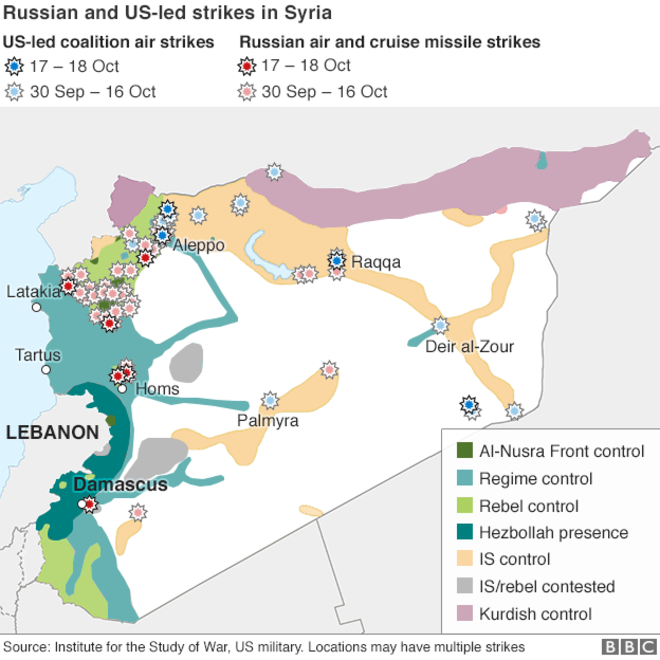

3. A Conflict Mapping Guide of Syria [7]

Syria is no longer a unified state. Assad’s government only controls the western coastal strip of Syria, and Syria’s borders with Lebanon. The latter are reinforced by Hezbollah militiamen, sponsored by Iran. The rest of the country is divided as follows:

3.a Syria’s northern borders with Turkey are largely controlled by Kurdish forces except for an important stretch which is controlled by IS. IS uses this territory to conduct the profitable smuggling of armaments and refugees.

3.b The balance of the west and north-west of the country is contested by the secular Free Syrian Army; a myriad of anti-Assad militias; the semi-theocratic, Al-Qaeda-linked Al-Nusra; and the theocratic IS.

3.c The balance of Syria to the east is largely controlled by IS forces that are free to roam except in the fiercely protected, mountainous, border areas controlled by the Kurds.

4. The Geopolitics in Syria [8]

(1) There is an alignment between Shia regimes like Iran, Iranian-sponsored Lebanese HezbolIah, Iraq, and Assad’s Shia (Alawite) Government.

(2) There is an alliance opposing Assad composed of Sunni regimes in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Kuwait, and Jordan, and a diverse mix of militias. The first three countries appear to be covering all bases, supporting, at least initially theocratic IS, semi-theocratic Al-Nusra, and the secular Free Syrian Army.

(3) While projecting itself on the international stage, Russia is also supporting Assad to protect its valuable, leased Mediterranean, warm-water port of Tartus and its leased airbase at Latakia. Russia’s support includes the aerial bombing of Assad's enemies, including the West's allies, the FSA. As we shall see, Russia’s involvement might well serve as “a game-changer.” [9]

(4) Turkey, a non-Arab Sunni state, may be supporting the Sunnis on a qualified basis. They have, however, directly attacked the Kurdish Sunni forces, allegedly because the latter are militating for an autonomous, potentially petroleum-rich, Kurdistan stretching over regions in Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran.

(5) The Western powers - primarily the USA, UK, and France - are backing the secular Free Syrian Forces. Since they have been smitten by their previous experiences in Afghanistan, Iraq, and more recently Libya, they are hoping to shortly identify a “reliable, trustworthy leader” to replace the thus far “unacceptable” Assad.

(6) The Kurds are backing the Western powers on the presumption that their people’s formidable fighting contribution will be prospectively recognized through the granting of greater regional autonomy during negotiations ending the conflict.

5. The Issues

The following issues were drawn up with the aid of: middleeast.about.com [10]

5a. Political Repression

Despite his earlier promises, Assad quickly dashed hopes of democratic reform, brutally opposing any form of protest. Under the circumstances, reform could only occur through an unlikely military coup or a popular uprising.

Theoretical Parallel - Hans Morgenthau's Theory of 'Power Politics' [11]

By Morgenthau's standards, Assad and his community of Alawite Shiites were governed by the principle of self-interest, as reflected in political power.

Evaluation: Morgenthau’s theory is static and substantive and nice-to-know.

5b. Discredited Ideology

Under Assad’s lead, the Syrian Baath Party was expected to merge the state-led economy with Pan-Arab nationalism. However, by 2000, Assad had reduced the Baath Party to an empty shell.

5c. Uneven Economy

Cautious reform of the remnants of socialism had opened the door to investment and an explosion of consumerism among the urban middle-classes. However, privatization had largely favoured families with personal links to Assad. This angered provincial Syrians who later led the uprising, as living costs soared and as jobs remained scarce.

Theoretical Parallel – Marxist ’Alienation’ [12] or Ted R. Gurr's Theory of 'Relative Deprivation' [13]

Political observers might conclude that provincial Syrians were probably driven to lead the uprising against Assad due to the frustration provoked by Marxist ‘Alienation’ or Gurr’s more contemporary theory of ‘Relative Deprivation'. Ted R. Gurr would have added that any 'deprivation' would have been ‘aspirational’, given that the expectations of provincial Syrians would have risen well above what Assad’s administration in the provinces was capable of providing.

Evaluation: Marx’s and Gurr’s theories both claim to be dynamic and substantive in nature. They are important to know but have generally been overshadowed by the combination of Azar-Burton theories.

5d. Drought

A persistent drought had devastated farming communities in north-eastern Syria, affecting more than a million people since 2008. Tens of thousands of impoverished farmer families flocked into rapidly expanding urban slums. Displaced farmers’ anger at the lack of effective government assistance was fueled by the ostentatious wealth of the nouveaux riches.

5e. Population Growth

Syria's has long possessed a rapidly growing young population. The bloated, unproductive public sector and the struggling private firms have been unable to absorb a million new arrivals to the job market every year.

5f. New Media

Since the new millennium, the previously tightly controlled state media have been unable to insulate youth from the outside world due to the proliferation of satellite TV, mobile phones, and the Internet. Use of the new media was critical to the activist networks that underpinned the Syrian uprising.

Theoretical Parallels - Anthony Obershall's Theory of 'Rising Expectations' [14] and James Duesenberry's 'Demonstration Effect' [15]

There is no doubt that Anthony Obershall might have credited the social media and Duesenberry’s 'International Demonstration Effect' with the rapid spread of the activist networks that helped foment the Syrian uprising.

Evaluation: Obershall’s and Duesenberry’s separate theories are ‘nice-to-cite’, especially when social media are involved.

5g. Corruption

'Speed money' is essential in Syria - whether to open a small shop or to register one's car. Those lacking either the money or the contacts develop a strong grievance against the state. The system is so corrupt that anti-Assad forces buy weapons from the government forces, and families bribe the authorities to release relatives that have been detained during the uprising.

5h. State Violence

Syria's vast intelligence services - the infamous 'mukhabarst' - penetrates all spheres of society. Although many Syrians feared the State, the outrage over the security forces’ brutal response to the students’ peaceful protest of Spring 2011 helped generate the massive uprising. More funerals generated greater protests.

5i. Minority Rule

Syria is a majority Sunni Muslim country. However, the top positions in the security apparatus are in the hands of the Alawis, a Shiite religious minority to which Assad’s family belongs. Although most Syrians pride themselves on their tradition of religious tolerance, many Sunnis still resent the fact that so much power is monopolized by a handful of Alawi families. Although not a driving force of the uprising, the combination of a majority Sunni protest movement and an Alawi-dominated military has added to the tension in religiously mixed areas, such as the city of Homs.

Theoretical Parallel - Ted R. Gurr's Theory of 'Relative Deprivation' [16]

Ted Gurr might have raised the probability that the majority Sunnis would have felt relatively deprived vis-à-vis the minority Shia Alawites that monopolized government power.

Evaluation: Ted Gurr’s ‘dynamic-substantive’ theory of ‘Relative Deprivation’ is important to know and apply, especially in fast-changing environments.

5j. Tunisia Effect

Last but not least, the wall of fear in Syria would not have been broken at this particular time had it not been for the self-immolation in December 2010 of the Tunisian street-vendor, Muhammed Bouazizi. The anti-government uprisings and the subsequent collapse of the Tunisian and Egyptian regimes in early 2011, broadcast live on the satellite channel Al-Jazeera, made millions in Syria aware that change was possible - for the first time in decades.

Theoretical Parallels - Anthony Obershall's Theory of 'Rising Expectations' [17] and James Duesenberry's 'Demonstration Effect' [18]

Obershall and Duesenberry would probably assume that the Theory of Rising Expectations and the International Demonstration Effect will have spread both expectations and the wave of protests across North Africa and the Gulf.

Evaluation: Obershall’s and Duesenberry’s separate theories are nice-to-cite, especially when social media are involved.

6. The Only Solution Possible

America and its allies find themselves in a bind in Syria. After their dismal experiences in Afghanistan, Iraq, and - more recently - Libya, they are concerned that, if they remove Assad – “the Devil they know”, they may end up confronting an even more worrisome Devil that they don't know. So, although they are assisting the Free Syrian Army with airstrikes ('airborne counterinsurgency'), war materiel, and military training, they do so tepidly and without conviction. In fact, President Obama admitted recently, somewhat enigmatically, that "he never wanted (to train the rebels in the first place) and has now been vindicated in his original judgment." [19]

It should be clear by now that continued violence, with ever more parties joining the fray, will only bring further destruction. The parties should negotiate: the hard-nosed and principled negotiations involving the U.S., Russia, China, Great Britain, France, and Germany around Iran stand as a remarkable example of how nations can resolve conflict with diplomacy instead of bloodshed.

Philip Gordon, former White House Coordinator for the Middle East, North Africa, and the Gulf Region, has laid out a blueprint for how such negotiations might proceed on Syria. [20]

(1) All the International players would have to be brought to the table, possibly under the aegis of the UN. These players would include Russia, Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Since this group includes supporters as well as detractors of Assad, they should first focus on common interests before deciding about his fate.

(2) There are common interests: de-escalating the violence, addressing the refugee crisis, and defunding & defeating IS. Shared objectives might, therefore, include:

- negotiating localized ceasefires between the government and rebel forces; &

- establishing a structure in which representatives of Assad's regime, including a new, jointly appointed, Council of Elders, could begin a dialogue with the rebels.

(3) The group of negotiating nations could then turn its focus to IS. A de-escalation of the civil war, paired with meaningful humanitarian aid and cohesive international efforts against IS, could prove the best hope for changing the fate and fortunes of the region. [The U.S. could show the way in terms of humanitarian assistance by offering to host a larger number of Syrian refugees.]

Theoretical Parallel – I. William Zartman’s ‘Hurting Stalemate’ Theory [21]

Owing to Russia’s increased involvement in Syria in recent months, the war may be fast approaching what William Zartman calls the ‘Mutually Hurting Stalemate’ (MHS) – a situation in which the two sides of a conflict – the Syrian government and the Syrian rebels – are able to hurt each other militarily, but with neither possessing the power to win completely over the other. Zartman adds that the time will be ripe for the start of talks, when the parties themselves observe that they face an impasse. In the case of Syria, given the numbers and the diversity of the parties involved, it would appear desirable that these talks are mediated by a mutually acceptable, independent third party.

Evaluation: William Zartman’s theory is important because it helps explain why certain intractable crises become malleable, sometimes overnight.

7. A General Caveat on Social Theories [22]

Philosopher Stephen Turner [22] salutes us with this final caveat: “Social science theories are better understood as models that work in a limited range of settings, rather than (as) laws of science which hold and apply universally.”

Mark Miceli-Farrugia 24-10-15

-----o-o-o-----

References

[1] Lucy Rodgers, David Gritten, James Offer and Patrick Asare's, 'Syria: The story of the conflict.', BBC News, 12 March 2015;

[2] Edward Azar, 'The Management of Protracted Social Conflict: Theory & Cases', Aldershot, Dartmouth, 1990.

[3] Lucy Rodgers, David Gritten, James Offer and Patrick Asare, op.cit.

[4] Ian Wishart, ‘Every Day’s a Crisis for Europe as Merkel Heads Back to Brussels, Bloomberg View, October 22, 2015.

[5] John Burton, 'Conflict Resolution - The Human Dimension', The International Journal of Peace Studies, January 1998.

[6] Michael B Kelley, 'The Madness of the Syria Proxy War in One Chart', Business Insider, October 16, 2013.

[7] ‘Battle of Iraq and Syria in maps’, BBC Middle East Report, 21 October, 2015.

[8] Reva Bhalla, 'The Geopolitics of the Syrian Civil War', Geopolitical Weekly, Stratfor, January 21, 2014

[9] Jim Muir, ‘Putin defends Russia’s air strikes’, BBC Middle East Report, 12 October 2015. Muir was quoting an ostensibly negative assessment of Russia’s wide-ranging aerial strikes by the EU’s foreign affairs chief, Federica Mogherini, on 5 October, 2015. As we shall discuss, Mogherini might have understated the real impact of Russia’s involvement.

[10] Primoz Manfreda, 'Top Ten Reasons for the Syrian Uprising', middleeast.about.com

[11] Hans Morgenthau, 'Politics Among Nations: the next steps in theory development' The International Journal of Peace Studies, Spring 2001.

[12] Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels, ‘The Communist Manifesto 1884’, Penguin Classics

[13] Ted R. Gurr, 'Why Men Rebel', Princeton University Press, 1970.

[14] Anthony Obershall, 'Rising Expectations and Political Turmoil' Journal of Development Studies, 1968.

[15] James S. Duesenberry, 'Income, Saving, and the Theory of Consumer Behavior', Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1949.

[16] Ted R. Gurr, op.cit.

[17] Anthony Obershall, op.cit.

[18] James S. Duesenberry, op.cit.

[19] Peter Baker, New York Times, quoted by Jo Comerford and Mattea Kramer, Tom Dispatch.com, 'Dealing with the Syrian Quagmire', October 18, 2015.

[20] Jo Comerford and Mattea Kramer, Tom Dispatch.com, 'Dealing with the Syrian Quagmire', October 18, 2015.

[21] I. William Zartman. ‘Ripeness: The Hurting Stalemate and Beyond’, Chapter 6, International Conflict Resolution After the Cold War, The National Academies Press, 2000.

[22] Stephen Turner, ‘The social theory of practices: Tradition, tacit knowledge, and presuppositions’, University of Chicago Press, 1994.

MMF – 24-10-15

-----o-o-o-----

Ratings